The most significant difference between bird banding and other methods is that it allows us to (reliably) identify each individual bird.

So what can we learn from this research?

Table of Contents

- 1. Bird Migration

- 2. Age and Life Span of Birds

- 3. Bird Morphology and Taxonomy

- 4. Regional Avifaunas

- 5. Change in population and habitat

- 6. What bird banding has revealed about some species

1. Bird Migration

Barn swallows banded in Japan and later recovered abroad. |

Bird migration has been a mystery to people since ancient times. Why do many of the birds we see in summer disappear in winter? The famous Greek philosopher Aristotle believed that swallows hibernated in hollow trees or in the mud of marshes. In recent years, even after the concept of migration became commonly accepted, people still wonder if swallows nesting under the eaves of their houses in summer are the same ones that nested the previous year and if they will return the next year. They also wonder how the swallows migrate and which route they take. Many questions remain to be answered. |

Which bird migrates the longest distance?

How far do migratory birds fly? Some species migrate long distances and some short, depending on the species. Some of the long-distance migrants are known to fly almost half way around the world from their home to their wintering site and back. This fact was first proven by bird-banding. In Japan, a seabird called the South Polar Skua (Stercorarius maccormicki) is presently the record holder for the longest migration distance among birds migrating to Japan. The bird had been banded in the Antarctic and had crossed the equator to end up offshore of Hokkaido—a distance of 12,800 km. |

2. Age and Life Span of Birds

|

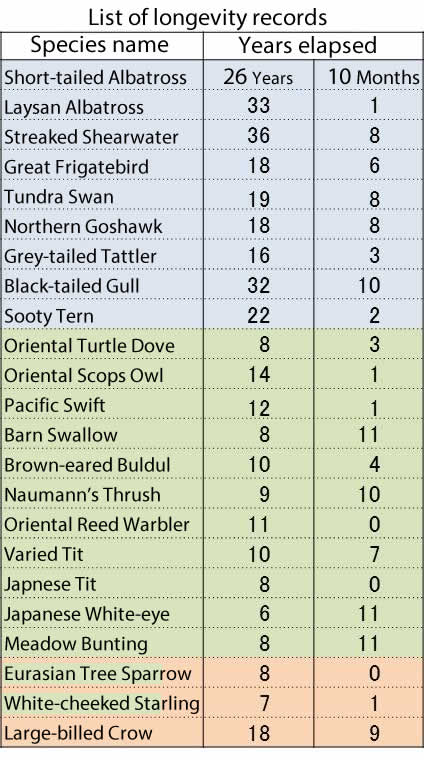

It is very difficult to determine the life span of wild birds. Therefore, to estimate their longevity, data on the amount of time that has elapsed between the banding date and the date when they are recovered becomes important. This method does not always allow for determination of a bird’s precise age since some birds are already adults when they are banded; however, the data can be used to prove how long they have survived from the date indicated on the band. Of 447 species of birds that had been banded during 38 years from 1961 to 1998, 125 species have been recovered five or more years after banding. The table on the right shows a list of longevity records of major species as of 2012. The list reveals that it is rare for small birds to live more than 10 years and that larger birds, particularly seabird species, often live longer. |

|

Which bird lives the longest?

|

What bird species holds the longevity record in Japan? A Streaked Shearwater that was banded in May 1975 in Kanmuri-jima, Kyoto Prefecture, was found in a weakened condition and rescued in January 2012, on Borneo Island, Malaysia after 36 years and 8 months. It is known that birds born in Kanmuri-jima generally return to the island four or more years later, and this bird was already an adult when it was banded. Based on these facts, we can assume that the bird was more than 40 years old when it was rescued on Borneo Island. In recent years, metal bands with improved resistance to corrosion and abrasion have been used, which may enable us to identify birds with a longer lifespan. |

|

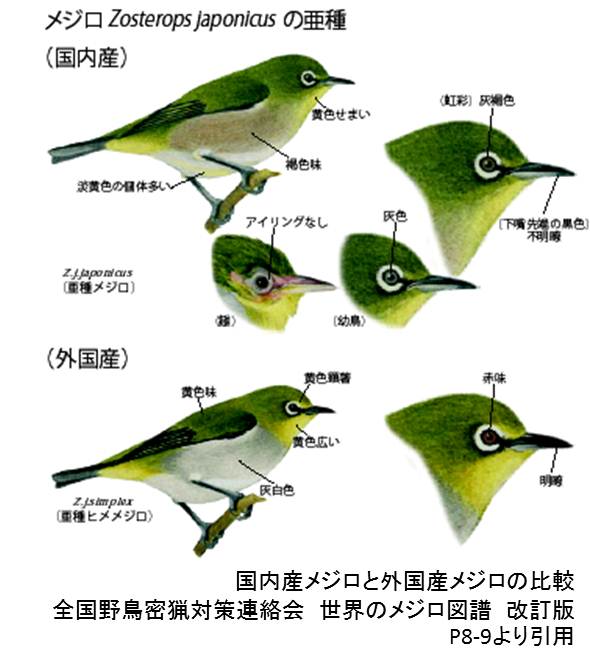

3. Bird Morphology and Taxonomy

|

A widely distributed bird species may, under careful observation, contain individual birds with slight variations that can be considered a different subspecies. Sometimes, the differences may be significant, leading to classification of a new species. Species and subspecies both require adequate protection on a local scale. This kind of study is based on ecological differences such as differences in song; morphological differences including measurements of various parts and wing color; and, most recently, DNA data analysis. Because many types of measurement data cannot be obtained from specimens or observations, banding surveys provide important opportunities to this end. |

Banding Survey Identifies a New Species: the Okinawa Rail (Gallirallus okinawae)

|

In carrying out bird banding surveys, researchers from the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology observed an unidentified Rallidae-type bird in Okinawa for three consecutive years from 1978. However, because this bird only appeared for short stints, they were unable to obtain detailed information. In 1981, the Bird Migration Research Center of Yamashina Institute conducted a survey to capture and determine the species of this elusive bird. During the study, one juvenile bird was captured on June 28 and one adult on July 4. After detailed observations were made, including measurements and photographic recordings, the two birds were banded and released. A research paper based on these study records, as well as information obtained from a separately found specimen that had died, was published, culminating in the official discovery of a new species, the Okinawa Rail (Gallirallus okinawae). This was the first discovery of a new bird species in Japan in almost 100 years, since the discovery of the Okinawa Woodpecker (Sapheopipo noguchii) in 1887. |

Okinawa Rail (Gallirallus okinawae) |

4. Regional Avifaunas

|

When considering the conservation of a certain region, local avifauna is one of the basic research items employed. Bird banding is a very useful technique to define species that are difficult to identify in the field such as snipes, and to detect secretive or nocturnal species that are extremely difficult to observe such as Locustellidae. |

Latham’s Snipe (Gallinago hardwickii) |

First Recorded Species in Japan from Bird Banding

|

Of the wild birds recorded in Japan, more than 15 species, including the Meadow Pipit (Anthus pratensis), Band-bellied Crake (Porzana paykullii), Wood Warbler (Phylloscopus sibilatrix), Little Swift (Apus nipalensis) and Red-breasted Flycatcher (Ficedula albicilla), were first recorded from bird banding activities. It is also effective to combine bird banding with other census methods when identifying avifauna and listing species present in specific regions, as the technique is able to record species that are difficult to observe. |

5. Change in population and habitat

|

A continuous banding survey performed at the same site using a standardized method allows researchers to identify the population trends of a certain species. When an environment changes, the area’s avifauna may also change. In recent years, more emphasis than ever has been placed on the use of bird banding data in environmental monitoring worldwide. In the U.K. and the U.S., researchers have been accumulating data at hundreds of survey sites nationwide since the 1980s. In Japan, changes in species composition and population trends of some bird species have been revealed from data accumulated from bird banding stations where research is conducted on a continuous basis. |

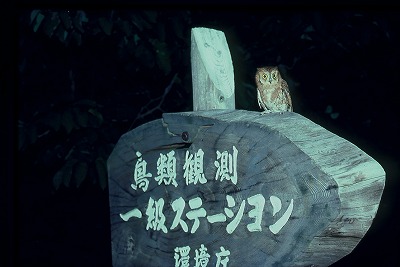

Scops Owl (Otus sunia)

|

Data obtained at bird observation stations

|

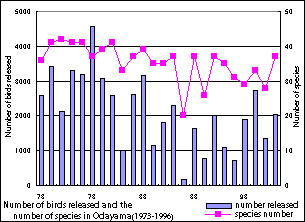

There are several sites in Japan where bird banding has continued since the 1970s. Data collected at these sites have been analyzed gradually. For example, at Odayama in Fukui Prefecture, species composition was seen to change significantly due to a sudden alteration in the vegetation in the area as a result of logging of the surrounding forest in the early 1980s. From a breeding season survey that has been conducted since 1973 at Lake Yamanaka, the ratio of summer birds was found to decline year by year since 1989. |

|

6. What bird banding has revealed about some species

The following facts pertaining to the following species have been uncovered as a result of bird banding:

Cattle Egret(Bubulcus ibis)・Intermediate Egret(Egretta intermedia)・Little Egret(Egretta garzetta)

Cattle Egrets and Intermediate Egrets, which are summer birds, breed in Japan and most of them move to the south in the winter. The Philippines was found to be the most important migratory stopover or wintering area for these species. Little Egrets were previously considered as a resident species; however, it has been found that some individuals migrate to distant wintering areas, including the Philippines.

Mute Swan(Cygnus olor)

Mute Swans are an introduced species of captive origin in Japan. Banding studies have revealed that Mute Swans breeding in Japan migrate regularly between summer and winter habitats.

Northern Pintail(Anas acuta)

It was found that while the breeding range of Northern Pintails is very wide, wintering birds in Japan come mostly from northeastern Russia; that individuals that usually overwinter in Japan sometimes do so in North America; and that there are small numbers of individuals that migrate from the western part of the Eurasian Continent.

Hooded Crane(Grus monacha)・White-naped Crane(Grus vipio)

Recovery records of metal bands attached to Hooded Cranes and White-naped Cranes are scarce. However, combined use of numbered color-bands enabled the collection of many observation records, thus allowing the identification of breeding areas and stopover sites of the two species that winter in Japan.

Ruddy Turnstone(Arenaria interpres)

In Japan, many Ruddy Turnstones are banded or recaptured in spring, but very few remain in the fall. It is therefore believed that this species, which is released in summer at St. George Island in the Bering Sea, mainly migrates to wintering sites in the South Pacific without passing through Japan, then flies northward along the Japanese archipelago in spring via a different route than the southward route.

Red-necked Stint(Calidris ruficollis)

Recovery records from metal bands attached to Red-necked Stints are scarce. However, through the use of small color-flags, dozens of observation records were reported for flagged Red-necked Stints. Based on these records, it was determined that the birds passing through Japan in the spring and fall overwinter at the Australian coast.

Black-tailed Gull(Larus crassirostris)

A long-term survey of the Black-tailed Gull at a breeding site in Aomori Prefecture has shown that they first move to the north from the breeding site after completing their breeding cycle, and move southward to the Kanto Region or further west in winter, and to the north again in spring. Additionally, some individuals were found to breed in areas different from their birth place.

Barn Swallow(Hirundo rustica)

Barn Swallows are summer birds in Japan. Their wintering range is quite wide, but banding recoveries showed that those migrating to Japan mainly winter in the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, and southern Vietnam, and that Taiwan is an important stopover site.

White Wagtail(Motacilla alba)

In Japan, White Wagtails previously bred mainly in Hokkaido and northern Honshu. It is believed that they started to breed commonly on the lowlands in middle Honshu and southwards since the early 1970s, and breeding distribution rapidly extended to western Honshu and northern Kyushu. This extension of the breeding range has been shown in records of banded recoveries.

Bull-headed Shrike(Lanius bucephalus)

We see Bull-headed Shrikes throughout the year in Japan as a resident bird. Surveys showed, however, that quite a few of them migrate long distances between the breeding and wintering periods.

Marsh Grassbird (Locustella pryeri)

The Marsh Grassbird is designated as a national endangered species and only a few breeding sites are known in Japan. Banding records have newly identified some wintering sites.

European Penduline Tit (Remiz pendulinus)

The Penduline Tit is a winter migrant to Japan. They were known to winter in Kyushu and the western part of the Chugoku Region until the mid-1980s. Banding surveys have shown that distribution of the species rapidly extended eastwards in ensuing years, and was observed in the Kanto Region after only 10 years.

Reed Bunting(Emberiza schoeniclus)

In Japan, Reed Buntings breed in the Tohoku Region and northward, and winter in Honshu and southward. Banding recovery records of Reed Buntings are extremely abundant compared to other small-sized birds. These records show that many individuals move from north to south along the Pacific coast and the Japan Sea coast in the fall migration season, but that there are also quite a few individuals that move inland from the Hokuriku Region to the Kanto and Tokai Regions. Some individuals also appear to migrate eastward from the Korean Peninsula via northern Kyushu.

Eurasian Tree Sparrow(Passer montanus)

The Eurasian Tree Sparrow is popular bird in Japan and can be observed throughout the year as a resident bird. A banding survey showed that quite a few individuals move a long distance from their breeding site in the wintering season.